David Wilcox

Bloomberg

August 16, 2024

Over the past four quarters, the US has enjoyed a solid run of real GDP growth. That could be a statistical blip that will be revised away as the Bureau of Economic Analysis refines its estimates. But if it survives, it will be a surprising development — because over the same period, the unemployment rate has crept up.

The combination of solid GDP growth and a rising unemployment rate suggests potential GDP growth — the pace at which real GDP can increase without generating an increase in inflation pressure — may have risen to an astonishingly high level.

- Over the four quarters ending in 2Q24, real GDP is estimated to have increased 3.1%.

- Ordinarily, that would be regarded as a sturdy performance. However, it wasn’t fast enough to prevent the labor market from weakening: Over the same period, the unemployment rate increased by 0.4 percentage point.

- One rough calculation suggests an additional 0.5 ppt of real GDP growth would have been enough to hold the unemployment rate steady.

- If that calculation is accurate — and if the current estimate of real GDP growth holds up — analysts may someday conclude potential GDP growth was 3.6% over the four quarters ending in 2Q24. That sounds implausibly high — but even if only part of that boost survives the revision process, you’d be left with a significant increment to the nation’s productive capacity.

To be sure, the fact that the unemployment rate increased noticeably despite apparently solid real GDP growth may be nothing more than statistical noise. In future vintages of the GDP estimates, it could be revised away.

If it’s real, this development could be another manifestation of the much-discussed recent surge in immigration. Alternatively, it could represent an early indication that AI is boosting productivity growth. Much more data will be required to sort through the various possibilities. If a productivity surge turns out to be the underlying cause — and that surge proves durable — the implications for the Fed, investors, workers, and governments will be profound.

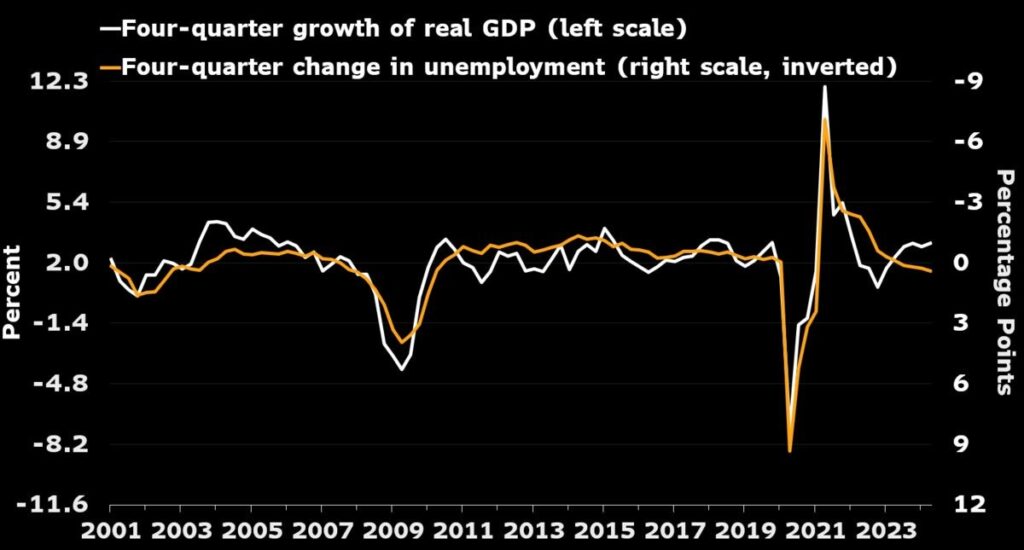

GDP Growth of 3.1% Not Enough to Keep Unemployment From Rising

Source: BEA, BLS, Bloomberg Economics

As shown in the graph, changes in the unemployment rate have been closely related to real GDP growth in the past. The four-quarter change in the unemployment rate is shown by the orange line and is plotted against the right scale, which is inverted.

- Since the turn of the century, a steady unemployment rate — zero on the right-hand scale — has been associated with roughly 2% real GDP growth, shown in the graph by the white line.

- Increases in the unemployment rate — shown by downward movements in the orange line, given the inverted right scale — have been associated with slower GDP growth, and conversely.

- Gauging the relationship over the period 2001-‘19 — thus excluding the Covid collapse and its aftermath — a 1-ppt increase in the four-quarter growth of real GDP has been associated, on average, with a 0.9-ppt decrease in the unemployment rate.

By the standards of many macroeconomic relationships, this one has been reasonably sturdy, but it was knocked off kilter by the Covid upheaval. Some other macro relationships appear to be coming back into more normal alignment. Whether this one follows suit could have profound implications.

Implications

Much depends on whether the surprising divergence between GDP growth and unemployment is real — and if so, how long it persists. If it proves to be a statistical mirage, then it signifies nothing — other than, perhaps, another reason to invest more in our collective ability to accurately measure the economy.

If the divergence reflects a productivity boom, and that boom has some staying power, the implications could be vast:

- For the Fed, it could signal that monetary policymakers shouldn’t allow solid GDP growth to deter them from beginning to cut policy rates. On the contrary, solid growth would be needed to prevent even faster softening in labor-market conditions.

- For investors, a prolonged productivity surge could rationalize equity valuations that otherwise might look unduly lofty — as was the case in the late-1990s.

- For workers, it could herald faster gains in their standard of living — depending on how the gains are distributed across the income distribution.

- For governments, a sustained productivity renaissance could ease fiscal pressures, as more revenues are collected off stronger incomes and less spending is required for social safety-net functions. A stronger growth outlook wouldn’t cure the ominous outlook for federal debt, but would at least push it in the right direction.

Robert Solow Would Be Surprised

Through the 1980s, there was painfully little evidence that the ubiquitous presence of computers was having any beneficial effect on productivity growth — prompting Nobel laureate Robert Solow to remark: “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.”

It can be dangerous to assume this time is different. For one thing, the apparent strength in GDP growth could be revised away as the BEA refines its estimates in coming years. (See here for more information about the magnitude of revisions to GDP estimates.)

But we shouldn’t rule out the possibility that this time will indeed be different. It’s possible that AI can be more easily integrated into existing work processes than was the case for computerization in earlier times – and if so, the benefits might manifest more quickly. Unfortunately, no one will know with confidence the national significance of this development for years to come.

Methodology

The scaling of real GDP growth in the graph is based on a regression of the four-quarter growth of real GDP on an intercept and the four-quarter change in the unemployment rate. The regression is estimated using quarterly data from 1Q2001 through 4Q2019.

The estimated coefficients are used to determine the scaling on the left-hand side that gives GDP growth the best fit to the unemployment variable.

The inverse of the slope coefficient from this regression is used to estimate the increment to real GDP growth that would have held the unemployment rate steady over the past four quarters.