Christopher Anstey

Bloomberg

October 6, 2023

- Ex-Treasury chief says Fed hikes may not be working as in past

- Summers says supply-demand imbalance helping drive yields up

Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers said the surge in US job growth last month is “great news” for now but also suggests the Federal Reserve’s interest-rate hikes aren’t working as they used to, raising the danger of a hard landing for the economy.

“We’ve got something of an ‘Energizer bunny’ economy,” Summers said on Bloomberg Television’s Wall Street Week with David Westin, referring to an ad campaign for a super long-lasting battery. But with job growth if anything accelerating, it makes the hard landing risk perhaps “look a little greater,” he said.

Summers spoke after data released Friday that showed US payrolls surged by almost double what economists had expected for September. The 336,000 gain came on top of upward revisions to hiring for the prior two months, though the report also featured a slowing in wage gains.

“You’ve got to recognize that these are good numbers, but I can’t say that they give anything like assurance of a soft landing,” said Summers, a Harvard University professor and paid contributor to Bloomberg TV.

“We may be living in a world where the interest rate is less of a tool for guiding the economy than it used to be,” Summers said. “That means when things need to be cooled off, interest rates are going to have to be more volatile than they have been in the past.”

He also warned that, with the current selloff in the bond market alongside risks from China and elevated valuations in many markets including private equity, “I see more dry tinder for financial flames than I’ve seen in quite a long time.”

“We’ve got to make sure that we’re thinking about contingency planning for our financial risk,” he said, urging policymakers gathering next week at a global confab to address “contingency for financial crisis.”

As for why the US economy may be less sensitive to interest rates, Summers noted the dynamic where, because many homeowners locked in low mortgage rates in previous years, they’re now less likely to sell. That reduces the inventory of homes, and drives up property values, which makes people feel wealthier, and helps sustain spending.

Causes of Change

Higher rates also means “more money in people’s pockets,” Summers noted. Meantime, some business investment, such as that in artificial intelligence, takes less time to implement, which makes it less sensitive to the level of interest rates.

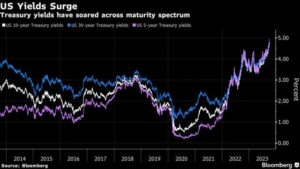

Summers attributed about half of the jump in US Treasury yields lately to a recognition by investors of “what’s going to be necessary to keep the economy in balance” given how strong growth has been. The so-called neutral level for the Fed’s benchmark rate, where it neither stokes nor slows growth, is now being revised higher, he said.

Ten-year yields climbed as high as 4.89% after Friday’s jobs numbers, the highest level since before the global financial crisis began in 2007. That’s about 1 percentage point higher than the start of the year.

Summers said the other key driver of the selloff in Treasuries has been an imbalance between supply and demand. The federal budget deficit is on track to roughly double for the 2023 fiscal year, forcing the Treasury to issue significantly more debt.

‘Big Effect’

Meantime, Summers highlighted that foreign investors including Japanese may have diminished demand for US government securitiesthanks to higher rates at home. Plus, US banks are less willing to stockpile Treasuries after mark-to-market losses on such holdings sank Silicon Valley Bank in March.

“So if you’ve got more supply and less demand,” then that’s “got to have a big effect on price,” Summers said.

Given the dynamics in train, “I don’t think interest rates are likely to come down quite as much” as markets anticipate, Summers said. “I wouldn’t be surprised if the market revises its view a little more.”

He also criticized the Fed and Treasury for failing to take advantage of the situation when rates were low to extend the maturity of public-sector borrowing. While companies and households were locking in low rates for longer, US financial authorities were effectively doing the reverse, he said.

QE Legacy

Summers said that the Fed’s past quantitative easing — when it injected liquidity into the economy by purchasing trillions of dollars of Treasuries — has meant a higher borrowing cost for the public sector, because the Fed pays an elevated short-term rate on the reserves that were created by QE.

“We’ve got a wall of higher and higher debts” ahead, he said. “We’ve got to have some serious discussions about the cumulating unsustainable path of fiscal policy in much of the industrialized world,” he added, hoping such talks occur when global finance chiefs gather next week for annual meetings of the IMF and World Bank.