Earlier this year, economists and Federal Reserve officials predicted that the U.S. economy would be sputtering by now as higher interest rates cut into spending and investment.

The opposite is happening.

Recent economic data suggest the economy is accelerating despite higher borrowing costs, the resumption of student-loan payments, and wars in Ukraine and the Middle East.

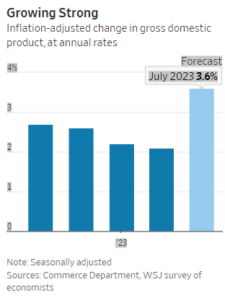

Analysts, many of whom had expected a recession this year, are pushing up their forecasts. Goldman Sachs economists last week raised their growth estimate for the third quarter ended on Sept. 30 to an annual rate of 4% from 3.7%. High Frequency Economics, an economic consulting firm, raised its third-quarter forecast to 4.6% from 4.4% and its fourth-quarter forecast to 1.2% from 1%.

A figure in that forecast range for the third quarter would represent acceleration from 2.2% growth in the first quarter and 2.1% in the second. The Commerce Department reports the official figure on Thursday.

A banner September

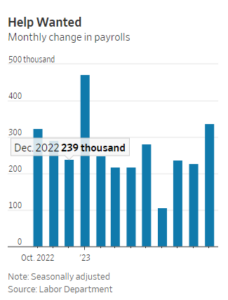

By some measures, the labor market actually got stronger over the course of the third quarter. Employers added 336,000 jobs in September, up sharply from 227,000 in August and 236,000 in July.

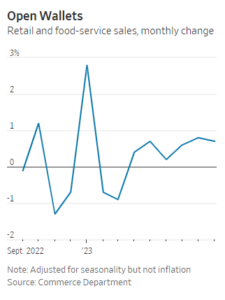

That hiring is fueling new spending. Monthly retail and food-service sales were up 0.7% in September after 0.8% in August, 0.6% in July and 0.2% in June.

Big banks such as Citigroup and JPMorgan Chase reported strong earnings this month, and executives say their outlook on the economy has improved. American Airlines also said Thursday that it expects travel demand this holiday season to be stronger than last year’s.

Despite this momentum, inflation has continued to ease, to 3.7% in September from a recent peak of 9.1% in June of last year.

That has allowed Fed officials to indicate they would hold off on further rate increases unless they see signs of renewed price pressures. The Fed has raised interest rates to a 22-year high of between 5.25% and 5.5% over the past 19 months to cool the economy and bring inflation under control.

Fed officials are “proceeding carefully,” Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said in a speech Thursday.

Investors are reacting to the momentum by pushing up yields on Treasury securities, assuming the strong economy will cause the Federal Reserve to hold off on interest rate cuts. The yield on the 10-year Treasury note topped 5% Monday for the first time since 2007.

Falling inflation boosts purchasing power

There are several possible drivers for the recent acceleration. First, the combination of cooler inflation and still-strong wage increases means that paychecks go further.

Between December and June, inflation-adjusted incomes after taxes rose at an annualized rate of 7%, estimates Ian Shepherdson, chief economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics. That pushed up the household saving rate to 5.3% in May from 3.4% in December of last year, adding to the roughly $1.2 trillion in accumulated savings left over from pandemic-era stimulus programs.

During the third quarter, households began to run down those savings, fueling new spending. The saving rate fell to 3.9% in August.

Receding fears of a recession could also be making households more comfortable spending money, especially now that it appears the economy has shrugged off the effect of the failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank in the spring, said Marc Giannoni, chief U.S. economist at Barclays.

After predicting a recession for the past year, economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal this month said they now believe that the economy will avoid a downturn in the next 12 months.

Muted impact of higher rates

Meanwhile, the Fed’s interest-rate increases haven’t had the expected cooling effect. That could be because businesses and households locked in lower interest rates during the pandemic when the Fed’s short-term rate target was near zero, Powell said Thursday.

Indeed, economists at Jefferies found corporate interest expenses as a share of revenue has been declining over the past year, despite the Fed’s rate increases. And while higher mortgage rates make it harder to finance new home purchases, roughly 14 million homeowners refinanced during the pandemic, according to research by the New York Fed.

That lowered many families’ mortgage payments and, in some cases, allowed them to cash out some home equity, boosting household savings by about $400 billion through the second quarter, the bank found.

Where does the economy go from here? Economists point to three possible outcomes.

First, the momentum might be short-lived.

Even though hourly wages are going up, workers are working fewer hours. Year-over-year weekly wages adjusted for inflation fell 0.2% in September, the first decline since May. If this continues, households could pull back.

Second, the economy could continue to run hot and send inflation up again. That could prompt the Fed to raise interest rates further, slowing the economy and raising the risk of recession.

A Goldilocks scenario

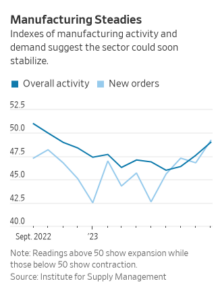

Third, growth could stay strong but inflation remain under control. This would be the best of all worlds because it would imply higher productivity, meaning that the economy could produce more goods and services without bottlenecks that lead to inflation. If that is the case, stronger growth could continue without the Fed having to raise interest rates.

There are some signs of promise. The proportion of working-age people in the labor force—that is, who are working or looking for work—is the highest in more than two decades. That suggests job growth can stay high without employers having to boost wages so much that they must also raise prices.

And the transition to cleaner energy sources is sparking new business investment, thanks to federal subsidies. Private-sector nonresidential spending amounted to 14.7% of inflation-adjusted gross domestic product in the second quarter of this year, the highest share in records going back to 2007.

For now, however, many economists are reluctant to embrace this upbeat scenario.

“Has the economy shifted in such a way that we don’t have to worry about inflation pressures from a tight labor market? I don’t think that’s the case,” said Ben Herzon, an economist at S&P Global.