James Mackintosh

The Wall Street Journal

September 15, 2023

The amount companies earn from cash in the bank is going up even as interest costs fixed during the pandemic stand still.

The Federal Reserve jacked up interest rates to slow the red-hot economy. At some of the biggest and most secure companies, the moves had the opposite of the intended effect, boosting their profits and spending power.

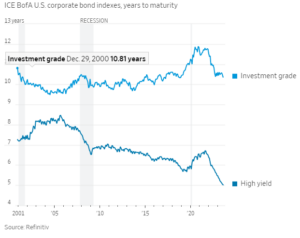

The winners from higher rates were high-quality borrowers, who locked in low interest rates around the pandemic with bonds maturing further in the future than any time this century. Higher rates have little immediate impact on their borrowing costs—only affecting bonds when they are refinanced—while they earn more on their cash piles straight away.

For the Fed, the dynamic blunts the impact of rate increases, which are meant to work in part by persuading big companies that capital is more expensive so they should pull in their horns. Companies that find they have more money thanks to higher rates can raise dividends, invest more and be more willing to pay up for the right staff, all supporting the economy.

Interest Impact

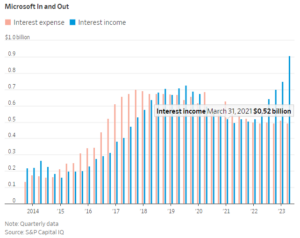

Companies are earning more in interest than they are paying out since Fed rate hikes.

Take Microsoft, the world’s second-most valuable company. It has more cash and short-term investments than debt, so it was never going to be threatened by higher rates. But it has also fixed its borrowing costs: It paid exactly the same interest, $492 million, in the latest quarter as a year earlier. However, it earned substantially more on its cash and short-term investments, with the annualized rate rising to about 3.3% from 2.1%; combined with a small increase in its hoard to $111 billion, it earned $905 million in interest just in the quarter, up from $552 million.

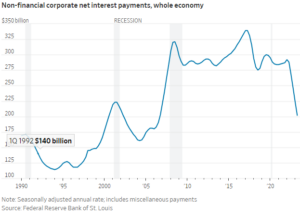

Microsoft’s experience appears to be reflected economywide. Corporate net interest payments—that is, interest paid on debt minus that received on savings—fell as interest rates rose, the opposite of what usually happens.

There is still corporate pain from higher rates, of course, and that has created a split between the haves and have-nots in the market. The pain falls on weaker companies that were unable to lock in low rates for very long, or that chose to borrow using floating-rate bank loans or similar debt where rates rise as the Fed hikes. Companies rated as junk, the weakest category, now have the shortest-ever maturity on their debt on average, meaning they face more frequent refinancing at much higher rates. More money spent on interest means less available for shareholders, workers and investment.

Even for weaker companies, there has been relatively little pain so far. Defaults and bankruptcies are up but far from catastrophic. Christian Stracke, president of Californian fund manager Pimco, says companies have been benefiting from higher inflation that supported profit margins, making higher rates easier to cope with. “Real [after inflation] interest rates have only recently gone positive,” he says.

“If we keep rates where they are now and there continues to be a cooling of the economy then there will be real stress if not distress in the leveraged credit market.”

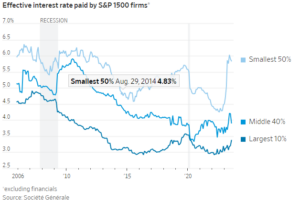

Split the market by size and it is clear that the biggest companies are the least affected by higher rates. Calculations by Andrew Lapthorne, head of quantitative research at Société Générale, show that the interest rate being paid by the largest 10th of companies in the S&P 1500 index is barely up from its lows and still below its prepandemic peak. The rate paid by the smallest half of companies in the index has risen to the highest in more than a decade, while those in the middle are roughly back at prepandemic rates.

Making the Fed’s job trickier still is that a similar pattern has supported consumers. Those who locked in low mortgage rates—with some securing the lowest rates ever in 2021—are, like Microsoft, paying the same on their debt while earning more on their savings. But those who didn’t qualify for standard mortgages, or who chose adjustable-rate loans, or need to borrow now, are suffering from the Fed’s rate hikes.

Of course, nothing is forever. The disparity between the winners and losers from rate increases provides yet another reason why the biggest stocks—the winners—have been by farthe best performers this year.

But threats to the dynamic loom: Time and the economy. The longer the Fed keeps rates high, the more bonds of even the best-quality issuers will have to be refinanced at a higher cost. And if the economy finally breaks, cyclical companies—those most sensitive to downturns, such as carmakers—faced with sharply lower cashflows will struggle to pay even low interest rates they locked in long ago.

Until then, we live in strange times. Rising rates make a big part of the economy feel richer—not poorer.